Playing sloppily and out of time is the biggest musical turn-off. Too sloppy, and it stops feeling like music. A lot of guitarists, me included, have struggled with timing. And I’m not talking about getting odd time signatures right intuitively. I’m talking about hitting notes on the beat and maintaining it – no speeding up, no slowing down, good ol’ consistent playing.

The classic advice is practicing with a metronome, which is rarely motivating or effective if you struggle to even perceive that you are off. Therefore, I propose a bypass-metronome approach that looks at how the brain and body anchor your timing for riffs and rhythms. The end goal is the same – make playing on time intuitive.

These alternatives to metronome practice are equally efficient in improving rhythm sense.

Let’s get straight to it.

Chapters

1. Tap your foot or move your neck

Sense of timing is related to repetitive body movements. Use your body to keep track. Practice tapping your foot or moving your neck to a metronome. The brain is excellent at multitasking with the body. So, when you outsource your timing process to a large muscle, it works separately and doesn’t interfere with playing. Moreover, the muscle movement itself becomes a perfectly coordinated cycle of muscles firing and contracting at a perfectly steady pace. Use body movements to create a timing reference.

If that feels odd, do a micro dance or body motion that somehow mimics the rhythm. Remember – the sense of time is in the body, not just the mind.

2. Partition your Riff

Complex riffs need to be broken down into chunks that feel easy. Get the groove for those, and then combine. Chunking is a concept you should be familiar with. Chunking is breaking down a long riff into small components, but not necessarily by bar or measure – in any way that’s meaningful to you. Chunk a riff in a way that every easy part is connected to something that throws you off. This ensures that you can start playing your chunk and focus all of your attention on the tricky part.

If it is equally difficult to play the entire riff, break it down into physically easy segments and practice those.

3. Use vocal substitutes

Forget the riff, first hum, and sing the riff correctly on time. The brain captures timing through voice better than untrained fingers; so it is much easier to hum melodies and grooves than play them out. Use your humming or singing as a scaffold and reference point to align your riff and vocalizing. If that is still difficult, follow a recording of your own voice.

4. Use the lowest notes possible

If you can practice a shape on a lower tuning, do it. The brain understands time better at lower sound frequencies. This is the reason why bass is groovy, and it’s easier to pick up the raw rhythmic structure with bass notes.

5. Trust muscle memory for tightness

Your brain has to trust muscle memory to correct its errors naturally. Make adjustments without looking at the fretboard. When your eyes look away, your brain is forced to optimize tactile (touch) and auditory signals. Visual signals can get distracting. Continue practicing without looking at your riffs till they become muscle memory. As you continue repeating, the movement becomes automatic and starts self-correcting.

6. Use the “BONOBOBO” technique

Consider a 4-beat bar. Assume you can play 16 notes in that bar – no offbeats or triplets for now. Each syllable – Bo, No, Bo, Bo represents a note. So your 16-note bar will effectively be BONOBOBO BONOBOBO BONOBOBO BONOBOBO. Speak your rhythm as syllables first. Change the pacing of the words to match the beat.

You can convert this to 3 notes per beat to as BONOBO BONOBO BONOBO BONOBO. Or 2 notes BONO BONO BONO BONO.

Syllables are language, and timing is embedded in language. This practice is particularly useful if you are switching from 1 or 2 notes per beat to 4. When you go double time, sing out your rhythm as BONOBONO for each BONO. Then, match the notes on the guitar while speaking the syllables.

7. Use a backing track or programmed drums

If a metronome is stressful, use a -1 track, drum loop, or programmed drums. The brain likes context. Metronomes don’t give context. An elaborate drumbeat helps you have the groove in which you play the riff. That makes more sense to the brain than just the metronome because it is now more musical and coherent.

More sense = easier processing. So, counterintuitively, it is easier to process time even if more details are contained in the whole drum + guitar combo than the metronome + guitar combo.

8. Get accurate feedback from recording

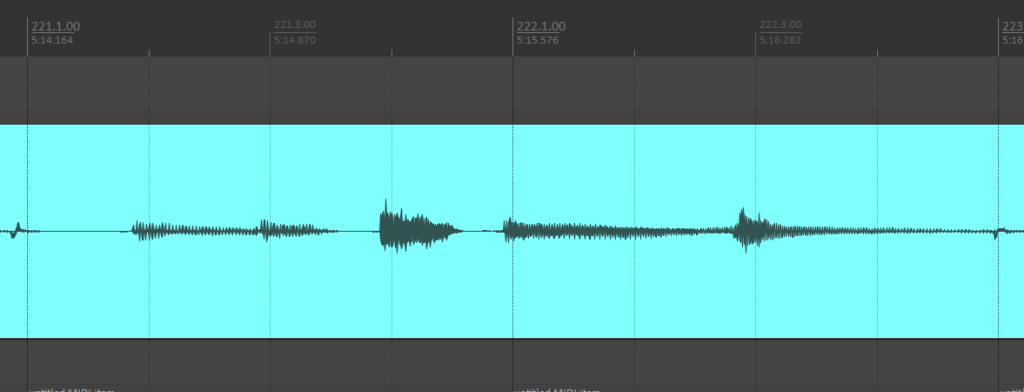

If you are unsure why your riffing is feeling off but can’t figure it out how, look at the recording wave patterns. Use a DAW like Reaper. You’ll notice how notes appear on a grid marked by milliseconds/seconds and beat counts. Then, you can figure out what parts of your riff land before or after the beat, and by how much.

The image below is a zoomed-in snippet of my recording. All of the notes land a little too early. This is my timing bias; I land early. A delay of 10 milliseconds before or after the beat is indistinguishable for simple rhythms. Greater than 20ms, and it’s noticeable. The delay in my recording below is -32 seconds; that’s 32 milliseconds before the correct time. Some people react slowly and land after the beat. Some anticipate too quickly and land early, like I did. Sometimes, the riff is complex, so low finger dexterity and lack of smooth fretting force an unusual delay.

Credits: Cover Photo by Edward Eyer: https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-playing-guitar-811838/